The process of choosing the best telescope for your needs can be overwhelming. We put together the following resources to help you make an informed decision. ![]() We suggest starting by watching our helpful video, How to Choose a Beginning Telescope

We suggest starting by watching our helpful video, How to Choose a Beginning Telescope

The process of choosing the best telescope for your needs can be overwhelming. We put together the following resources to help you make an informed decision. We suggest starting by watching our helpful video, How to Choose a Beginning Telescope, and then reading the article below.

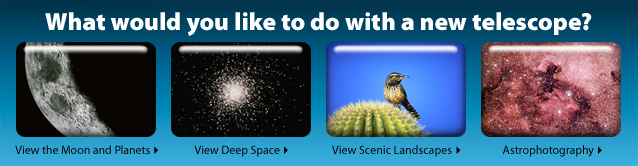

People all around the world enjoy looking at the stars of the night sky. There are many different telescope designs available, but what telescope is the best choice for someone just starting out? The question of which telescope is best for a beginner is asked quite often, and the best person to answer the question is you! The telescope that's right for you will depend on your lifestyle and your astronomy goals. To help steer you in the right direction, let's review the major factors to consider.

1) Performance — What will I be able to see?

Performance is perhaps the most important factor when choosing a telescope. Knowing what you can expect to see through the telescope can help determine which instrument is right for you. The aperture, or diameter, of a telescope governs how much light the telescope can collect. A larger aperture telescope will be able to collect more light than a smaller diameter instrument, and therefore will be able to show you a larger number of night sky objects and more detail on them. Also, a telescope with a larger aperture can be pushed to a higher viewing magnification compared to a smaller diameter scope.

Telescopes measuring 60-80mm (2-3 inches) in aperture will provide nice views of the Moon, bright planets like Jupiter and Saturn, and a few of the brighter cloudy nebulas and star clusters. A telescope with an aperture of 90-130mm (3.5-5 inches) will show a substantial increase in detail on the same subjects, and allow you to see more dim objects in the sky, like galaxies, some of the more faint nebulas and star clusters. Telescopes with apertures of 150mm (6 inches) and above are capable of providing very bright and sharply detailed views of solar system objects and most deep space objects like cloudy nebulas, sparkling star clusters, and distant galaxies.

Every increase in aperture, no matter how small, will have an exponential effect on performance. A 10-inch telescope will show more than an 8-inch model, which will show more than a 6-inch, and so on. Of course, the larger the telescope's aperture: the larger the telescope. Don't forget to weigh your decision of telescope aperture with the size and portability factor.

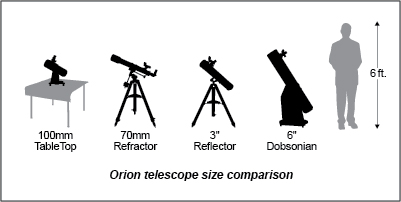

2) Size and Portability

An old saying in amateur astronomy is "the best telescope is one that is used often." Like many sayings, it has a lot of truth to it. The size and relative portability of a telescope can have a significant effect on how often you use it. While a larger telescope will usually allow you to see more, you may not want an especially large telescope if its size will prohibit you from using it regularly. Our advice is to pay close attention to the size and weight of the telescopes you consider, and try to anticipate how much effort each one will take to set up and use. If you have any concerns about the size of a particular telescope, there is a good chance Orion has a slightly smaller model with similar characteristics and features. Although some telescope designs can be bulky, many observers find the extra effort worth it to obtain beautiful views of the heavens.

3) Optical Design — Which telescope design is best for me?

While most people think of a pirate with an eye-patch wielding a long brass tube when we hear the word "telescope", there are actually many different optical designs used to make telescopes. The three most common telescope designs are: refractors, reflectors, and Cassegrains. Each design has different attributes that may make one more enticing to you compared to another, depending on your goals. Let's briefly investigate each design and their main differentiating factors to help you make an informed decision on which one is right for you.

Refractor

Refractors are the oldest telescope design. A small refractor of 60mm to 80mm diameter, referred to as aperture, is usually what most beginners consider buying as a first telescope, thanks to their recognizable appearance and history of good performance. Refractors use a lens system to collect and bend, or refract, light into a cone shape that is focused in an eyepiece for you to view.

A refractor is an excellent choice if you'll be doing most of your stargazing from the city or suburbs, where night skies are moderately light polluted. Since they use a lens system, refractors can be equipped with accessories for daytime use taking in magnified views of terrestrial objects like birds, wildlife, and scenery. Refractors require little to no maintenance, since their optical elements are fixed in place and cannot be misaligned during normal use. Renowned for crisp, sharp images, refractors are the priciest per inch of aperture of all three most common types of telescope, but they are arguably the most user-friendly as well.

Here are some refractor telescopes we recommend for beginning astronomers:

- Orion Observer II 70mm Altazimuth Refractor Telescope Kit

- Orion Observer 80ST 80mm Equatorial Refractor Telescope Kit

- Orion BX90 EQ 90mm Equatorial Refractor Telescope

Reflector

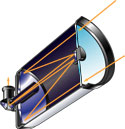

As their name implies, reflector telescopes reflect light to a focus point by using mirror based optics. Collected light is reflected off a large dish-shaped parabolic primary mirror, and then reflected again off a smaller secondary mirror so you can focus the view in an eyepiece.

Reflectors provide a big performance punch in a very affordable package relative to other optical designs. All things considered, you will most likely get the most performance per dollar invested out of a reflector design. While affordable, reflectors do require more maintenance, which is an important consideration. Unlike refractor telescopes, the mirrors of a reflector can occasionally become misaligned if the telescope is roughly handled. Because of this, reflectors can sporadically require manual re-alignment, or collimation, of the optics. Don't let collimation intimidate you; any telescope owner can perform this task with a little practice.

Reflectors are most commonly offered in two ways: mounted to a tripod, or attached to a base. Base-mounted reflectors are known as "Dobsonian" designs, named after astronomer John Dobson who unveiled the first Dobsonian base-mounted telescope in 1978. Known as the "best bang for the buck" compared to other telescopes, a Dobsonian or tripod-equipped reflector will provide years of enjoyment for a comparably modest investment.

Here are some reflector models that would be excellent telescopes to begin a hobby of stargazing:

- Orion SkyScanner 100mm TableTop Reflector Telescope

- Orion SpaceProbe II 76mm Equatorial Reflector Telescope Kit

- Orion StarBlast II 4.5 EQ Reflector & AstroTrack Motor Drive

- Orion XT8 Classic Dobsonian Telescope & Beginner Barlow Kit

Cassegrain

Cassegrain telescopes are a relatively recent design compared to refractors and reflectors. Cassegrains are a more advanced and specialized telescope design that uses elements of both refractors and reflectors to bend and reflect collected light. This gives a Cassegrain telescope a very long focal length in a conveniently compact telescope tube.

There are numerous variations of Cassegrain telescopes available to amateurs, all based on the original design attributed to Laurent Cassegrain of France. Orion offers a selection of Maksutov-Cassegrains, which is a variation including elements of both Cassegrain and Maksutov telescope designs. The Maksutov telescope design is named after optician and astronomer Dmitrievich Maksutov of Russia. A Maksutov-Cassegrain (Mak-Cass for short) telescope excels at higher magnification study of relatively narrow-field objects, like the Moon, planets, bright nebulas and star clusters. If you anticipate spending a large amount of time viewing the Moon and planets, a Mak-Cass should be on your short-list of candidate beginner telescopes. Like refractors, Mak-Cass telescopes can be equipped with accessories to provide a correctly oriented daytime view of birds, scenery, and wildlife.

Here are some Maksutov-Cassegrain telescopes we feel are worth considering for beginners:

- Orion StarMax 90mm TableTop Maksutov-Cassegrain Telescope

- Orion Apex 102mm Maksutov-Cassegrain Telescope

- Orion StarSeeker IV 102mm GoTo Mak-Cass Telescope Kit

4) Price

Price is a very important factor, especially if you are just starting out as an astronomy enthusiast. You may not be certain you and your family will have a long-term interest in looking through a telescope, and therefore may not want to spend a lot on a first telescope. There are many reasonably priced, high-quality beginner's scopes that can reveal incredible wonders, while helping you define your particular viewing interest. Alternatively, if you feel your interest in amateur astronomy will last, investing in a more capable and more expensive telescope is worthwhile.

It doesn't matter if you have a large or small budget, Orion will have the right telescope for you and your family to start a rewarding hobby of stargazing together.

The Bottom Line

The question of what is the best beginner telescope depends on you and your goals in the hobby. We recommend you take advantage of information and resources such as our website and catalog to help you make the most appropriate selection for you and your family.

In closing, let's re-visit some of the most important factors to consider:

- Aperture — A telescope's aperture, or diameter, relates to what you'll be able to see and how much detail will be observable. Essentially: the larger the aperture, the more you'll see.

- Size and portability — The best telescope for you is the one you'll use most often. A huge, optically wonderful scope will bring little joy if it's always stuck in a closet!

- Optical design — Depending on your goals and budget, choosing one telescope optical design over another can help simplify your ultimate decision.

- Price — A modest investment in a telescope can provide years of family fun.

Be sure you don't forget the most important factor of all, to have FUN!

If you get stuck along the way, we're here to help you with any questions. Just send us an email or give us a call Toll-Free at 800-447-1001 and we'll help you find the right telescope!

The question of which telescope is best for the beginner is asked a lot. Here are our thoughts on the best beginner telescope — it really depends on what is important to you! There are many factors, most of which can only be answered by you, to pick the best beginner telescope. Here are some general guidelines to help steer you in the right direction.

Price, portability, what you can see with your new telescope and features such as computerized and GoTo functionality are the common attributes for the beginner to consider.

Price is a very important factor, especially if you are a beginning enthusiast. You may not be sure that you or your family will stick with the hobby for the long run and want an entry-level price just to get you started. Of course, you may find that in no time at all you're ready to step-up to a larger, more feature-rich telescope. Or, your high level of interest in astronomy and desire to have a high-quality, more capable telescope right from the beginning may make the investment in a higher-priced telescope your best choice. No matter your budget - Orion will have the right telescope for you!

The design and size of the telescope has a lot to do with portability and what you can see.

Refractors are the telescope design that most beginning astronomers consider first. A refractor uses a lens that provides a clear, quality view and tends to be smaller and more portable. Refractors can be used for both astronomy and scenic viewing (with a correct-image diagonal). A small 60mm-70mm refractor is one of the most inexpensive investments you can make to get into the hobby. You will be able to see the Moon in great detail, the rings of Saturn, and a cloud belt or two around Jupiter. Smaller telescopes are very portable and inexpensive, but lack the aperture (size of optics/light-gathering capability) needed to see much outside of the solar system like faint nebulae and galaxies.

Some great refractor choices from Orion can be found in the Refractor Telescopes For Beginners category.

If you're looking for the next step up to a more capable, feature-rich refractor, you can explore these Intermediate Refractors.

Reflectors use a primary and secondary mirror to gather light from the universe to your eyes. Mirrors are more economical to manufacture and are available in larger sizes to gather more light and see beyond our solar system. Reflectors are used exclusively for astronomy and tend to be a larger, less portable telescope.

There are relatively inexpensive models that will allow you to enter the realm of deep-sky objects, as well as give excellent views of the planets. A 4.5" to 8" Dobsonian is perhaps the best "bang-for the buck" beginner choice.

With a scope like this, you can see things like the Orion nebula in nice detail, the oval structure in the Andromeda Galaxy, the Ring Nebula in Lyra, and many more deep sky objects. Best of all, these telescopes are big enough in aperture that they will probably last many years before being out-grown.

Of course you can spend more to include computerized capability found in the GoTo and IntelliScope Dobsonians.

Cassegrains make a great portable telescope using a combination of mirrors and lenses. They are very portable, can be used for scenic viewing during the daytime with a correct image diagonal, and are available in larger aperture with less weight to manage.

Here are some great, entry-level Cassegrains for Beginners.

If price isn't quite as much of issue and you want to invest more but still don't want something overwhelmingly large, consider these Intermediate Orion Cassegrains.

As you can see, there are many different types of scopes that can be a great first telescope - consider a few of the factors we've described here before you make your decision and you can't go wrong.

Or just send us an email at sales@telescope.com, contact us via live chat, or give us a call Toll-Free at 800-447-1001 and we'll help you find the right telescope!

Like choosing neighborhoods, automobiles, or spouses, buying a first telescope is a highly subjective undertaking. There's no "best" telescope for everyone. The one that's right for you will depend on your lifestyle and your astronomy goals. Spending a little time analyzing your motivations will help you make an intelligent choice. Let's look at the different types of telescopes, and in so doing, some of the considerations that might influence your buying decision.

Power is Not the Important Thing

The first point to emphasize is that magnifying power is NOT the most important consideration when choosing a telescope. Not even close. It is the telescope's light-gathering capability, or aperture, that determines how much you will be able to see. Overblown claims of 450x or 575x power (or more!) in ads for inexpensive telescopes are pure baloney, and a sure sign of inferior quality. The brightest, sharpest images are obtained at much lower powers, on the order of 25x to 50x.

Refractors

Refractors

A small, quality achromatic refractor of 60mm to 80mm aperture makes a fine starter scope for observing the Moon and major planets. They're inexpensive ($100 to $350), portable, and maintenance-free — all desirable factors if you're just "testing the waters" of the hobby. Their small apertures aren't well suited for faint deep-sky objects, though. If nebulas and galaxies are your main interest, a Newtonian reflector or Schmidt-Cassegrain is the way to go. Moving up to a 90mm or 100mm refractor will snare more objects and provide better performance, for a higher price. Renowned for crisp, sharp images, refractors are the priciest per inch of aperture of all telescope types.

A refractor is the scope of choice if you will be doing most of your stargazing from city or suburbs, where the night skies are moderately light-polluted. Here, more aperture doesn't gain you much, since viewing is restricted mostly to the Moon and planets. In fact, a big scope would only amplify the skyglow, yielding poor washed out images.

Reflectors

Reflectors

Newtonian reflectors are great all-around scopes, offering generous apertures at affordable prices. They excel for both planetary and deep-sky viewing. Of course, the larger the aperture, the more you'll see. Smaller, 3" and 4.5" equatorially mounted Newtonians will provide a nice "survey" of celestial luminaries, and they're plenty portable. Six-inch and 8" Newts have enough aperture to deliver captivating images of fainter fare-clusters, galaxies, and nebulas-especially in a reasonably dark sky. The tradeoff is their bulk and weight — something you should definitely take into account before you buy. But a 6" Newtonian on a Dobsonian mount is easily manageable by one person, and makes a wonderful beginner scope. Dobsonian-mounted reflectors have lower price tags than their equatorial counterparts, starting in the mid-$300s for a 6" Dob.

Schmidt-Cassegrains

Schmidt-Cassegrains

If portability is important to you, you might want to consider a "catadioptric" scope such as a Schmidt-Cassegrain or Maksutov-Cassegrain. They pack a hefty aperture into a very compact tube. An 8" Schmidt-Cassegrain provides excellent views of the Moon, planets, and deep-sky objects, and is well suited for astrophotography. But an SC is a considerable investment for a beginner — over $1000 for the most basic 8" models (and hundreds more to outfit it for astrophotography). Although compact, an 8" SC is actually quite a lot of scope to manage when you include the beefy tripod and mount. So beware!

Telescope Mounts

A quick word about mounts. Telescopes come on three basic mount types: altazimuth, Dobsonian, or equatorial. The altazimuth is the simplest and is recommended for casual stargazing and terrestrial observing. The Dobsonian mount is a boxy altaz-type mount designed for easy maneuvering of large Newtonian tubes of 6" aperture or greater. Equatorial mounts are a bit more complicated (and more expensive) than altazimuth mounts, but allow the user to follow the motion of celestial objects with a single manual hand control, or even automatically with a motor drive — a great convenience.

The Bottom Line

OK, now that you've gotten the crash course on telescopes, here's some parting advice for aspiring astronomers:

Get as much aperture as you can reasonably handle, but not more.

Big aperture is desirable, sure, but you don't want to end up with a scope that is too big or complicated to conveniently set up, haul around-and use! Also, avoid those gee-whiz, techno-toy scopes with the hefty price tags that are showing up in the big chain stores. For a first telescope, we recommend a basic refractor of 90mm aperture or smaller, or a Newtonian reflector of 6" aperture or less, unless you're really committed. After you've learned the basics of observing and developed an appreciation for the hobby, then you can move up to a bigger, fancier scope.

Just send us an email at sales@telescope.com, contact us via live chat, or give us a call Toll-Free at 800-447-1001 and we'll help you find the right telescope!

Given the bewildering array of telescopes on the market, how does an enthusiastic but inexperienced consumer choose the right one? To answer this question we will explain the differences between specific telescope types, but for that discussion to be meaningful it is important first to understand some very basic points about astronomical telescopes in general.

Aperture is the Most Important Factor

The single most important specification for any astronomical telescope is its aperture. This term refers to the diameter of the telescope's main optical element, be it a lens or a mirror. A telescope's aperture relates directly to the two vital aspects of the scope's performance: its light-gathering power (which determines how bright objects viewed in the scope will appear), and its maximum resolving power (how much fine detail it can reveal). There are other criteria to be considered in selecting a telescope, but if you learn only one thing from this article, let it be this: the larger a telescope's aperture (i.e., the fatter it is), the more you will see.

Don't Get Hung Up on Power

Unfortunately, the first question most beginners ask is not "What is this telescope's aperture?" but "What is its magnifying power?" The truth is, any telescope can be made to provide almost any magnification, depending on what eyepiece is used. The factor that limits the highest power that can be used effectively on a given scope is, you may have guessed, its aperture. As magnification is increased, and the image in the scope grows larger, the light gathered by the telescope is spread over a larger area, so the image is dimmed. There is also an absolute limit, determined by the physical properties of light, to the resolution that is possible with any given aperture. As the magnification is pushed beyond that limit the image fails to reveal any additional detail and gradually breaks down into a dim, fuzzy blob.

The maximum useful magnification for any telescope is about 50 times the aperture in inches, or two times the aperture in millimeters. This equates to about 100x to 120x with the smallest telescopes, which is enough to see such wonders as the rings of Saturn and cloud bands on Jupiter. The 2x per millimeter figure is a rule of thumb, and can vary up or down somewhat depending on the optical quality of the scope in question and the vision of the individual observer. Experienced observers usually use much less power; 0.5x to 1x per millimeter is more appropriate for most objects. Any manufacturer claiming that their 60mm scope can provide good views at 450x (7.5 times the aperture in millimeters) is trying either to pull your leg or pick your pocket!

Bigger is Better, But...

While aperture is the most important specification of any telescope, there are exceptions to the rule that "bigger is better." One is obvious: the need for portability. The largest amateur telescopes are very big indeed, and demand either housing in a permanent observatory or possession of a strong back, a truck, and a gang of muscular and motivated observing buddies! There is a line to be drawn between performance and portability, and where it will be drawn varies with the individual and his or her capacity for storage and portage. Beginners are encouraged to start out with a scope of sufficient aperture to feed their interest, but of a size that they can manage easily. Avoid succumbing to "aperture fever." Those infected with this psychological malady choose the largest telescope they can afford without regard to portability. Their monster scopes soon gather dust in the garage, exiled for the crime of being too heavy and bulky, while the once enthusiastic would-be stargazers wind up frustrated or in traction.

The Sky IS the Limit

The second limitation on very large telescopes is less obvious, but becomes apparent after the first couple of viewing sessions: the Earth's atmosphere limits how much we can see. Stars and planets viewed through a telescope appear to shimmer or wiggle, as their light passes through the air and is distorted. This effect is known to astronomers as seeing, and becomes more noticeable and bothersome as telescope aperture increases. It especially affects observations of the Moon and planets, where high power applied to reveal fine details also magnifies the air turbulence.

The amount of distortion due to seeing varies, depending upon the behavior of air currents in the upper atmosphere, and to a lesser extent upon the altitude and topography of the observing site. But on an average night, at an average site, air turbulence will limit useful magnification to 250x or 300x, and prevent telescopes larger than about 8" or 10" aperture from achieving their full potential for high-powered viewing. Telescopes larger than 10" are most often chosen by observers who want to gather as much light as possible for viewing dim galaxies, nebulas, and star clusters. These "deep sky" objects, affectionately called "faint fuzzies," are most often viewed at much lower power than the planets, so seeing is less of a problem.

Telescope Mounts

The last important topic to cover before delving into optical designs is that of mounts. Telescopes are offered on either altitude-azimuth (or altaz) mounts, which move up-down (altitude), left-right (azimuth), or equatorial mounts, which are tilted to align with the rotational (polar) axis of the Earth.

Altaz mounts are generally lighter and simpler to use, and are preferred if the telescope is to be used both for astronomy and daytime observing (or for daytime observing only). The better ones offer slow-motion controls to aid in moving the scope by small increments, and are useful for powers up to about 150x. The Dobsonian mount is a variation on the altaz mount. It employs unconventional (for telescopes) materials like plywood and Teflon in a compact mounting that moves easily, is extremely stable, and can adequately support large telescopes at a very low cost. Though there are no mechanical slow-motions or electric drives on a Dobsonian, a well-made example glides so smoothly on the Teflon bearings that with a little practice it is quite easy to track objects manually at 200x or more!

Equatorial mounts are designed specially for astronomy, and are not recommended for terrestrial viewing. Their advantage is that they allow easier tracking of the stars across the sky. This motion can be achieved with either a single manual slow-motion control or an electric motor drive (or clock drive). The easier viewing they provide at high power makes equatorials preferred by observers who are most interested in the Moon and planets. Also, you'll need an equatorial mount if you want to do astrophotography.

Different Scopes for Different Folks

Now that we understand these basic points of telescope performance and mounting, we can discuss the three basic optical designs of telescopes: the refractor, the reflector, and the compound (or catadioptric) telescope.

A refractor is what most nonastronomers think of when they hear the word "telescope." Its tube is most often long and skinny, mounted on a tripod, with a lens at one end and the eyepiece at the other. Refractors were the first type of telescope invented, and the finest refractors still provide the best images of any design for a given aperture. They are often chosen by observers with a dominant interest in the planets and Moon, because they can provide sharp, high-contrast views at high magnification and are less bothered by atmospheric "seeing" than the other designs. They also require less maintenance than reflectors or compound scopes, and are therefore popular with beginners. The refractor's good performance at high power and relative insensitivity to light pollution makes it a good choice for a city-based observer, as the design performs best on the objects that are most easily seen from urban or suburban locations.

A refractor is what most nonastronomers think of when they hear the word "telescope." Its tube is most often long and skinny, mounted on a tripod, with a lens at one end and the eyepiece at the other. Refractors were the first type of telescope invented, and the finest refractors still provide the best images of any design for a given aperture. They are often chosen by observers with a dominant interest in the planets and Moon, because they can provide sharp, high-contrast views at high magnification and are less bothered by atmospheric "seeing" than the other designs. They also require less maintenance than reflectors or compound scopes, and are therefore popular with beginners. The refractor's good performance at high power and relative insensitivity to light pollution makes it a good choice for a city-based observer, as the design performs best on the objects that are most easily seen from urban or suburban locations.

These advantages do not come without a price—literally: refractors are the most expensive telescopes per inch of aperture. Big refractors can cost several thousand dollars, and still are considered too small in aperture for serious deep-sky observing. The long focal length of most refractors restricts the field of view, making it difficult to take in large extended objects like some clusters of stars. And the long tube, with the eyepiece located at the back end, requires a tall tripod, which, if poorly made, can allow the scope to shake and shimmy in the breeze, rendering high-powered observing difficult.

The reflector uses a mirror, rather than a lens, to gather and focus light. By far the most common design is the Newtonian reflector, which places a concave (dish-shaped) primary mirror at the bottom end of the telescope tube. A small secondary mirror at the other end directs the focused light out the side of the tube and into the eyepiece. Newtonians offer the largest aperture available at given price, and when well made, they can provide sharp, contrasty views that rival all but the finest refractors. A Newtonian's low center of gravity and eyepiece location at the top of the tube allow for comfortable viewing with a more compact mounting, which can be made stable with much less bulk and cost than the tall mounting required by a refractor of similar aperture.

The reflector uses a mirror, rather than a lens, to gather and focus light. By far the most common design is the Newtonian reflector, which places a concave (dish-shaped) primary mirror at the bottom end of the telescope tube. A small secondary mirror at the other end directs the focused light out the side of the tube and into the eyepiece. Newtonians offer the largest aperture available at given price, and when well made, they can provide sharp, contrasty views that rival all but the finest refractors. A Newtonian's low center of gravity and eyepiece location at the top of the tube allow for comfortable viewing with a more compact mounting, which can be made stable with much less bulk and cost than the tall mounting required by a refractor of similar aperture.

Big reflectors of 10" aperture and larger on Dobsonian mountings are the most popular telescopes for astronomers who seek to gather "buckets of light" for deep-sky observing. These giant scopes perform best at remote dark sky sites, away from the glare of city lights. The value and versatility of the smaller 4.5" to 8" Newtonians, mounted either equatorially or as Dobsonians, makes them a fine choice for the beginner with general interests.

Newtonian reflectors require occasional maintenance. Unlike the lenses in a refractor, the mirrors in a reflector need periodic alignment, or collimation, for best performance. While many beginners seem intimidated by collimation, it's really not difficult, and takes only a few minutes once you get the hang of it. A reflector's tube is also more open to air and humidity than that of a refractor, and if left uncovered the mirrors can accumulate dust and grime, which necessitates occasional cleaning. While these maintenance concerns are often overstated, a Newtonian may not be the right choice for someone who finds the prospect of occasional tinkering with the telescope unappealing.

The most modern of the three common designs for amateur telescopes is the compound, or catadioptric type, which uses a combination of lenses and mirrors to gather and focus light. The greatest advantage of this design is its compactness: the lenses and mirrors "fold up" the light path inside the telescope, reducing large-aperture scopes to a manageable size. If an equatorial mounting is desired, the smaller tube can be carried on lighter and more economical mounts than that required by a Newtonian of the same size. Compound telescopes are most popular with observers who desire both generous aperture and an equatorial mounting in a transportable package.

The most modern of the three common designs for amateur telescopes is the compound, or catadioptric type, which uses a combination of lenses and mirrors to gather and focus light. The greatest advantage of this design is its compactness: the lenses and mirrors "fold up" the light path inside the telescope, reducing large-aperture scopes to a manageable size. If an equatorial mounting is desired, the smaller tube can be carried on lighter and more economical mounts than that required by a Newtonian of the same size. Compound telescopes are most popular with observers who desire both generous aperture and an equatorial mounting in a transportable package.

The names Schmidt-Cassegrain and Maksutov-Cassegrain refer to specific designs of compound telescopes, which use differently shaped lenses and mirrors to achieve a similar result. The Maksutov is often cited as offering better image quality, though there is little in the way of optical theory to support this opinion. Most probably the Maksutov has developed its reputation as the superior catadioptric design because its spherical optical surfaces are easier to make to very high precision than the more complex shapes demanded by the Schmidt. As a result, if a telescope maker practices anything less than the strictest quality control, their "average" Maksutov will outperform their "average" Schmidt. In top-quality telescopes from careful manufacturers, both designs can yield excellent images.

There are a few drawbacks to all compound designs. As in any telescope that employs mirrors, occasional alignment is required for peak performance. The cost of a compound is higher than that of a Newtonian of the same aperture, though still lower than the cost of a comparably sized refractor. Most significantly for the planetary observer, the secondary mirror in a compound is much larger than that in a Newtonian, and its presence in the light path of the scope reduces contrast somewhat for high-powered viewing. In general, astronomers who desire a highly capable, easily transportable telescope find these worthwhile compromises, and have made the compound scopes very popular.

Price is a Consideration

Budget is a factor in almost every telescope purchase decision, but there are at least three major price-related pitfalls to be avoided.

1) Don't buy a flimsy, el cheapo scope at the mall with the intention of getting a taste of the sky and upgrading later. Many of those scopes are so poor-quality and frustrating that they can turn budding stargazers off of astronomy for good!

2) On the other hand, don't give up on astronomy if the scope of your dreams is financially out of reach at this moment. There are many reasonably priced, high-quality beginner's scopes that can reveal incredible wonders, while helping a novice define his or her particular observing interest.

3) Finally, if you are one of the fortunate few for whom price represents little obstacle, think twice before buying the biggest, most expensive telescope in stock. Many of the large, fully featured scopes favored by experienced observers are also the most complicated, and are too much to grasp for someone still trying to find the Big Dipper!

What About Astrophotography?

Before concluding, here's a quick word for the beginner who wants to jump right into astrophotography through their new telescope: Don't! At least, not until you have taken some time to learn the sky and become familiar with operating your scope. Photography of the heavens can be a wonderfully rewarding pastime, but is a combination of art and science with a steep learning curve that can discourage beginners who try to take on too much at once. Of course, if astrophotography is a primary interest there is nothing wrong with selecting a first scope based on its easy adaptability to camera work in the future. While most telescopes can be used for picture-taking (with varying prospects for success), the most important qualifications for a photographic instrument are a rock-solid equatorial mounting, and ease of attaching a camera so that it can be focused. For a variety of technical and economic reasons, compound telescopes of 8" aperture and larger are most popular for photography. They also make fine instruments for general observing.

The Bottom Line

Which, then, is the right telescope? That's a decision that must be made individually, but the three best pieces of advice are:

1) The best telescope for you is the one you will use most often. A huge, optically wonderful scope will bring no joy if it is consigned to the closet!

2) All else being equal, a larger-aperture (diameter) telescope will reveal more in the night sky than a smaller one ("I know, already!" you may be thinking.)

3) Buy from a company that's knowledgeable about telescopes and astronomy, and who will support you even after your purchase (since you will likely have questions).

Our advice is to select a well-made telescope, of a design matched as well as possible to your primary observing interest and most frequent observing site. Make sure it's a size that can be handled easily (by your standards and no one else's) and used often, and you will enjoy a lifetime of awe and wonder under the stars!

Just send us an email at sales@telescope.com, contact us via live chat, or give us a call Toll-Free at 800-447-1001 and we'll help you find the right telescope!